Anton Krupicka Takes On the LA Freeway Trail

This summer Anton Krupicka set the record for the LA Freeway Trail unsupported, in a single push, besting the previous FKT (fastest known time) by over 3 hours. He told us about his experience in his own words.

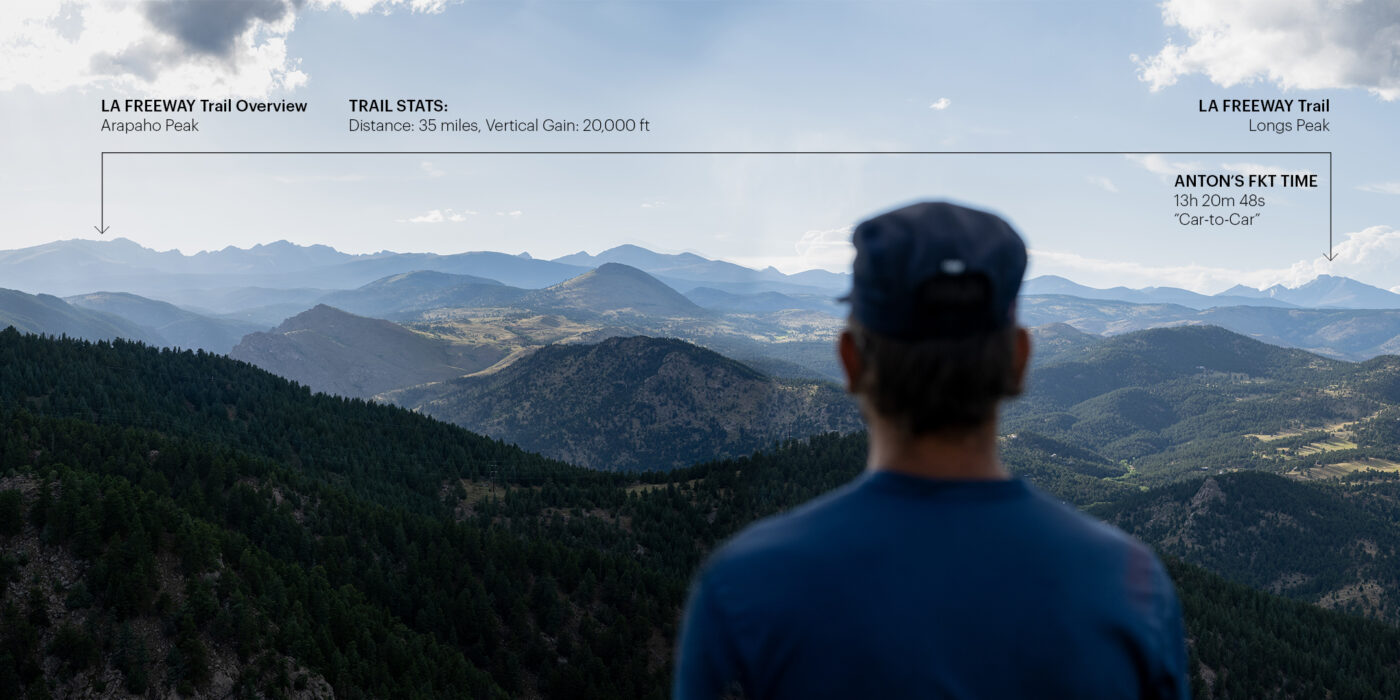

Two weeks before I made my run on the LA Freeway, I had a photoshoot with Smith Optics in Boulder, CO. We were posted up on a rocky outcrop high above town to the west, waiting for the sun to lower and the light to get nice. Typical photoshoot stuff. Our vantage happened to offer a particularly spectacular and comprehensive perspective of the traverse which comprises the LAF route—the 12,000-foot-and-higher Continental Divide ridge that runs from Longs Peak in Rocky Mountain National Park to Arapaho Peak in the adjacent Indian Peaks Wilderness. This section of the Divide cuts a striking profile visible from town. A high-altitude saw-blade of snow-capped summits that looms imperiously over the hustle and bustle of the Boulder Valley. A year-round reminder of summer ambitions for the qualified mountain runner.

Longs to Arapaho (LA Freeway, get it?), bookend a traverse with almost two dozen additional peaks on the Divide to be surmounted between them. All off-trail except for short bits of the initial approach and final egress. Technical scrambling and complex route-finding are required to overcome the many craggy obstacles along the way. Spiky and spicy, to be sure, but as our overlook was proving out, it is such a logical and inspiring link for someone with a mind to ultra-distance foot travel over beautiful, complicated, alpine terrain. For better or worse, I am someone with exactly that mind.

I couldn’t help but point out the objective to my companions—see that high summit? And that one? That whole skyline connecting them is what I’ve been training for all summer. My enthusiasm for the beauty and symmetry of it all, however, had at that moment been tempered internally by the knowledge that I’d already given up on making an attempt this year.

Two weeks previous, in early August, on a scouting run up on the Divide I’d discovered that after a very dry June and July, almost all available surface water on the route was gone. The route crosses no roads and intersects just two backcountry trails—my vision was to complete the 34-mile traverse in a single, unsupported push, meaning not meeting anyone along the way for resupply, nor caching food or water beforehand. Without seasonal springs and tundra pools to drink from and refill my flasks, an unsupported run was impossible, or would require periodically dropping several hundred feet below the Divide to dip from alpine lakes and streams. Not ideal.

Furthermore, just the day before the photoshoot, I had scrapped a high-alpine run because my Achilles tendon was hurting. My left Achilles has been a chronic problem for the past seven years, but, seemingly, had been mostly cooperative of late. After spending all summer attempting to gingerly tread the fine line between keeping it healthy while still training enough to be prepared, it felt like I’d finally overstepped in a way that would make undertaking the considerable rigors of the LAF route a non-starter. I suppose my mentioning the goal at all—despite any opportunity for attempting it having seemingly disintegrated—was an indicator of how meaningful an organizing principle the Freeway had become in my life over the summer. I tried to conceal my disappointment.

The representative from Smith on the shoot enthusiastically directed, “Get a shot of that! We need that picture for when Tony smashes the route!” I winced. I could feel my insides contract a bit, knowing that I wouldn’t even be able to try this season. I immediately wished I hadn’t said anything.

Two days later, though, a funny thing happened. On yet another otherwise typical run up Longs Peak—my 25th ascent of the year—my Achilles felt fine and my legs had curious pop and bounce, encouraging me to run hard. I obliged and snuck under the 2hr-mark for a roundtrip lap on the 14,259’ mountain, becoming only the third known person to ever do so. It was a huge personal best and the kind of effort I never dreamed I’d be able to achieve on Longs–-the crown jewel of Rocky Mountain National Park–-let alone at the athletically-advanced age of 41. I actually couldn’t believe it.

In the wake of my Longs Peak hot lap, I had a realization. All of my disappointment and downheartedness about not getting to attempt the LA Freeway was unnecessarily preemptive. There was still time. I could still choose to shape the conclusion to my summer.

Another, more practically motivated, shift in thinking happened that day on Longs: I noticed that little trickles on the mountain that had disappeared for the past month were starting to flow again. With my Achilles cooperating again and the possibility of water resupply on the full route renewed, maybe, just maybe I’d been premature in assessing that the window for an unsupported attempt had been closed.

A few days later, I made a final scouting run on the route and was surprised and delighted to find that the monsoonal rains in the alpine over the past month had completely replenished vital water sources on the Divide. “F— yeah!” I exclaimed to no one. I surprised myself with how much involuntary enthusiasm I was still carrying for the endeavor.

Four days later, I made my attempt, breaking the existing record by more than 3hrs, taking 13 hours and 20 minutes to cover the 34 miles and 18,000’ of elevation gain on the LA Freeway.

A big part of running’s attraction to me has always been the capacity it contains to shape our own destinies. As a teenager and 20-something I convinced myself that I actually possessed that kind of control over my life. With enough discipline and hard work, anything was possible, I thought. Looking back, I realize this is an immature and hubristric orientation to the world. Sure, some things are in our control, but, man, a lot of things really aren’t, and that’s ok.

Part of growing older, and maybe growing up, has been realizing that what is most important isn’t how we control the variables within our power, but rather how we adjust and adapt when life throws up the inevitable roadblock. Not necessarily what we achieve, but how we conduct ourselves in the pursuit of our dreams. That there’s a subtle but profound difference between persistence and patience. That waiting for the right moment is not tantamount to giving up. You can’t just brute-force everything.

For the past month since my run, the LA Freeway, of course, hasn’t gone anywhere. It still towers above town, implacable and indifferent, yet now, instead of serving as a reminder of a promise I hadn’t kept, it’s an affirmation of a dream fulfilled.