Connor Ryan and Natives Outdoors Are Making the Slopes More Inclusive

In honor of Native American Heritage month this November, Connor Ryan shares his experience in his own words as an Indigenous skier and how he’s working to make sure more Indigenous skiers and snowboarders have access and the resources they need to get out on the mountain.

Six winters ago, I sat on the chairlift with sunlight falling warmly across my face as I reached the top of a ridge. I thought about what run I’d ski as I stared at the slopes below me. The sign for the run I knew I’d choose gleamed in a way that seared my mind. My friend who sat beside me asked the question I hoped wasn’t coming but knew was inevitable. “Do you think you’re the only Native American who has skied down Indian Ridge?”

The black diamond run falls steeply into a mogul field, wearing a cornice like a crown. As much as I loved diving from its snowy ledge into a couple hundred feet of demanding bumps, I resented the name deeply. I knew my buddy had asked me the question in a way that was intended to highlight my prowess on snow and how proud he was of all the effort it had taken me to afford my ski gear and pass. However, for me at that moment, feeling special made me feel more alone than celebrated. I answered awkwardly, but what I said will never be as memorable to me as how it felt to be asked that question.

As Native Americans we are often included in the lore of the outdoors, but seldom in the present tense. The trouble is I was born in 1993 and I’ve only ever lived in the present moment. In the years since that day I’ve thought about that moment weekly. I’m always wondering why it is so hard for people who love the ski runs and climbing routes that criss-cross the lands Indigenous people call home to recognize us as contemporary humans. The names of the trails, sometimes for better but often for worse, reference us persistently. 26 of the states in the USA come from words in Indigenous languages or reference Native people. There are 574 federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native tribes in the United States, and 630 First Nations communities in Canada. However, most skiers and boarders I’ve met in my travels have never participated in outdoor recreation alongside someone from our tribes or communities. According to the Snowsports Industry Association we currently make up less than 0.5% of skiers and snowboarders.

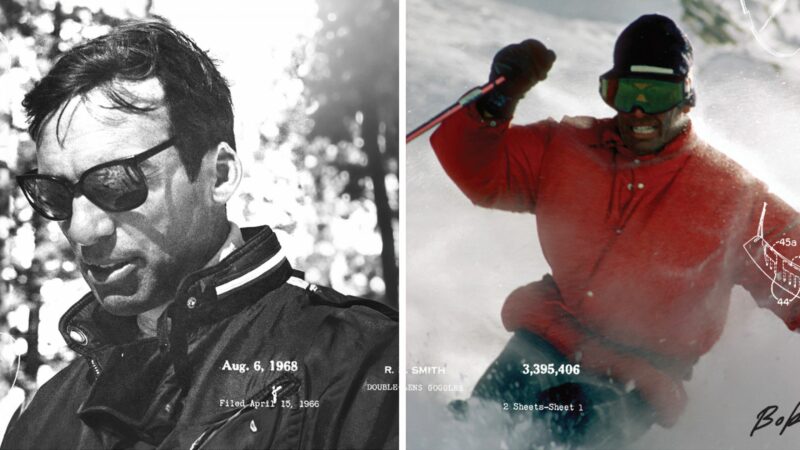

Even though the question my friend posed stung in the moment, the self-inquiry it led to has brought me a lot of healing. I was 23 years old when he asked me about skiing Indian Ridge, and despite having my first ski pass at 21, I was a professional skier by 27. I went on to be sponsored and paid by Smith Optics, Salomon, Patagonia, Hestra and the like. I was the first Native American to ski in and co-direct a major ski film, Spirit of the Peaks, which was selected by Mountainfilm and won Best Cinematography at 5 Point Film Fest. My desire to reach the place I’m at in the sport didn’t come from a competitive drive or ski town pedigree. I persistently pursued opportunities in skiing because I felt I had to show other skiers that Native American people still exist. Speaking to our shared love of the landscapes and ecology that make skiing possible was my way to make them acknowledge that they skied on Native land.

The privilege that comes from my success has brought an obligation. The values of my culture fly in the face of the excesses often associated with skiing and its locales. One of my first major brand partners was Ikon Pass, and I reached out to them not to see if they would do something to support me, but instead what they would do to support Native people as a whole. In the early winter of 2020, I reached out in frustration when I was unsure if the ski industry cared about the barriers to access the original inhabitants of the land face in trying to enjoy snow sports.

I sent an email at 4pm on a Friday to Ikon Pass and its competitor, never expecting a reply from either. To my surprise, I had a reply in my inbox by 4:15 from someone at Ikon Pass who I now consider a close friend. She asked if I could talk the next morning. My reaction was disbelief. “You’d like to talk to me at 9am on Saturday?”

A year after that conversation we were giving away 10 Ikon Passes to Native American folks across the country as part of a scholarship program created in collaboration with Natives Outdoors, an Indigenous outdoor media brand. The scholarship included all the gear required for skiing or boarding and lessons if necessary. By the second year the scholarship had grown to 15 and the gear given included a pair of my signature goggles. Smith Optics included me in their athlete collection and I collaborated with one of my uncles to put a beadwork pattern that represents our tribe’s connection to the mountains across the goggle strap. I got to see it worn proudly on the faces of other Indigenous skiers and boarders.

Today, I’m writing this between responding to emails to the 30 recipients of the scholarship for the 23/24 season. Smith Optics is still equipping every one of our Indigenous skiers and boarders who are receiving an Ikon Pass this year.

I talked to Anton Chamblee, an Inuit snowboarder, who was one of our recipients last season. He claims to have scored over 15 powder days in the Cottonwood Canyons before going to work the afternoon shift at an Indian Health Services funded clinic in Salt Lake City. He told me how after moving from Alaska to Utah, having so much time in the snow and on the land gave him a new sense of home. He shared this feeling of belonging by working to get Native youth from the community out to shred the slopes as part of the substance abuse prevention programs offered by the tribe he works for.

“It takes one of us who knows the value of being out there to know what it means to be able to pass it on to the next generation.” Anton told me as we reflected on how we hadn’t had the same opportunities as the kids he’s working with now. I was able to empower Anton’s connection and this year he’s written grants to grow the snow sports programs for the youth he works with.

This work is not always easy, and it’s not something most other pro skiers have to do, but I am grateful to be obligated by the land and my culture in this way. Sometimes there is a bit of grieving that comes with being able to pass on an opportunity that you did not have yourself, an uncertainty in sharing easier access to something you had difficulty attaining. I do wonder what the next generation of Native skiers and boarders will be like, what obstacles their connection to nature will help them overcome, what stories they will tell, and maybe even what ski movies they’ll make. But one thing I don’t ever wonder anymore is if I will be the only Native to ski down Indian Ridge.